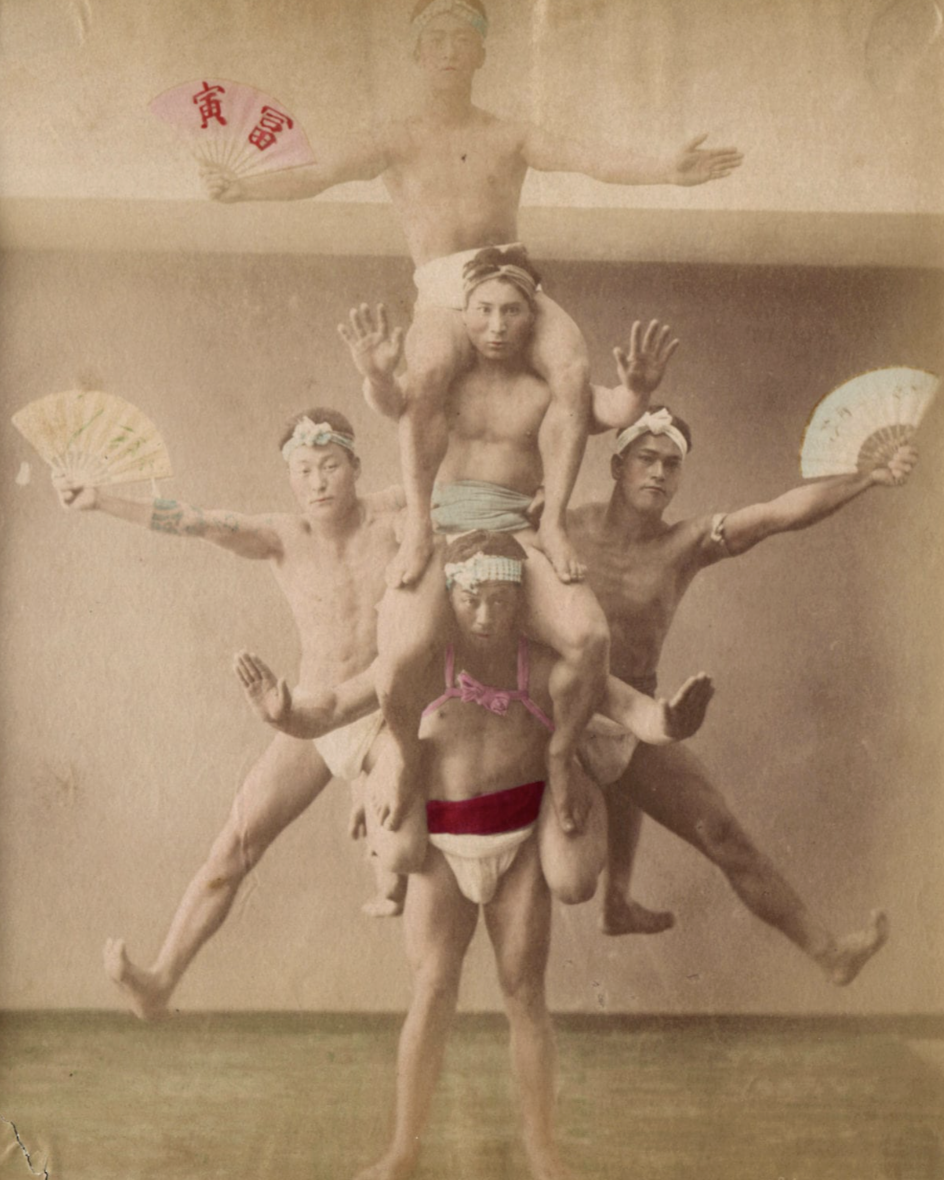

I came across Felice Beato again this week.

Again, because his images have been part of my visual vocabulary for a long time.I just hadn’t followed them back to the man.

Beato, an Italian–British photographer, was working across Asia at the end of the nineteenth century.

Among the first to photograph war.

Running a studio that developed its own methods for hand-colouring photographs, in collaboration with Japanese watercolour artists.

Learning that changed how I read the work.

The images didn’t change.

My distance from them did.

What I had taken as historical records began to read as deliberate constructions.Images made with an awareness of how they would circulate, how they would be seen.

It left me with a deeper appreciation, not just for the photographs,

but for the intention and labour behind them.

Sometimes that’s all it takes.

Not a new image.

Just the story around it.

The End & The Beginning

Happy New Year.

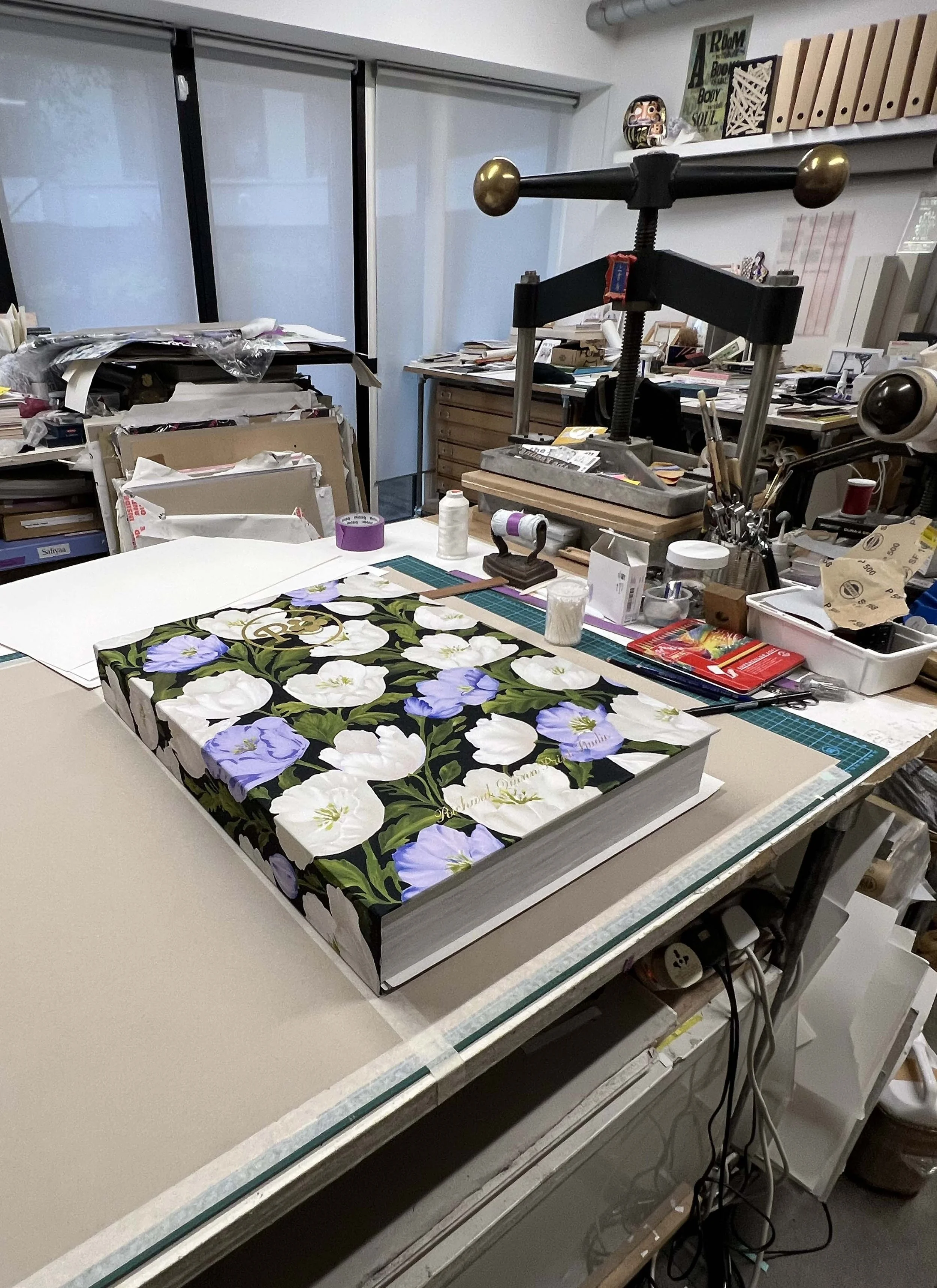

This was one of the last photos I took before the break.Under that pile of improvised weights there’s a book I can’t show (NDA): engraved marble front and back, sitting in a leather case.

Sometimes a job asks for more than what you already know.

You use what you have.You make it work.

Looking at it now, thinking about what’s next, I’m reminded how far resourcefulness carries the work.

You rarely have every tool, nor the right one.

If you stay calm and deal with the next constraint, things move.

A good reminder to start the year.

Less drama. More inventiveness. Same high standards.

Question: What’s one workaround you’re weirdly proud of?

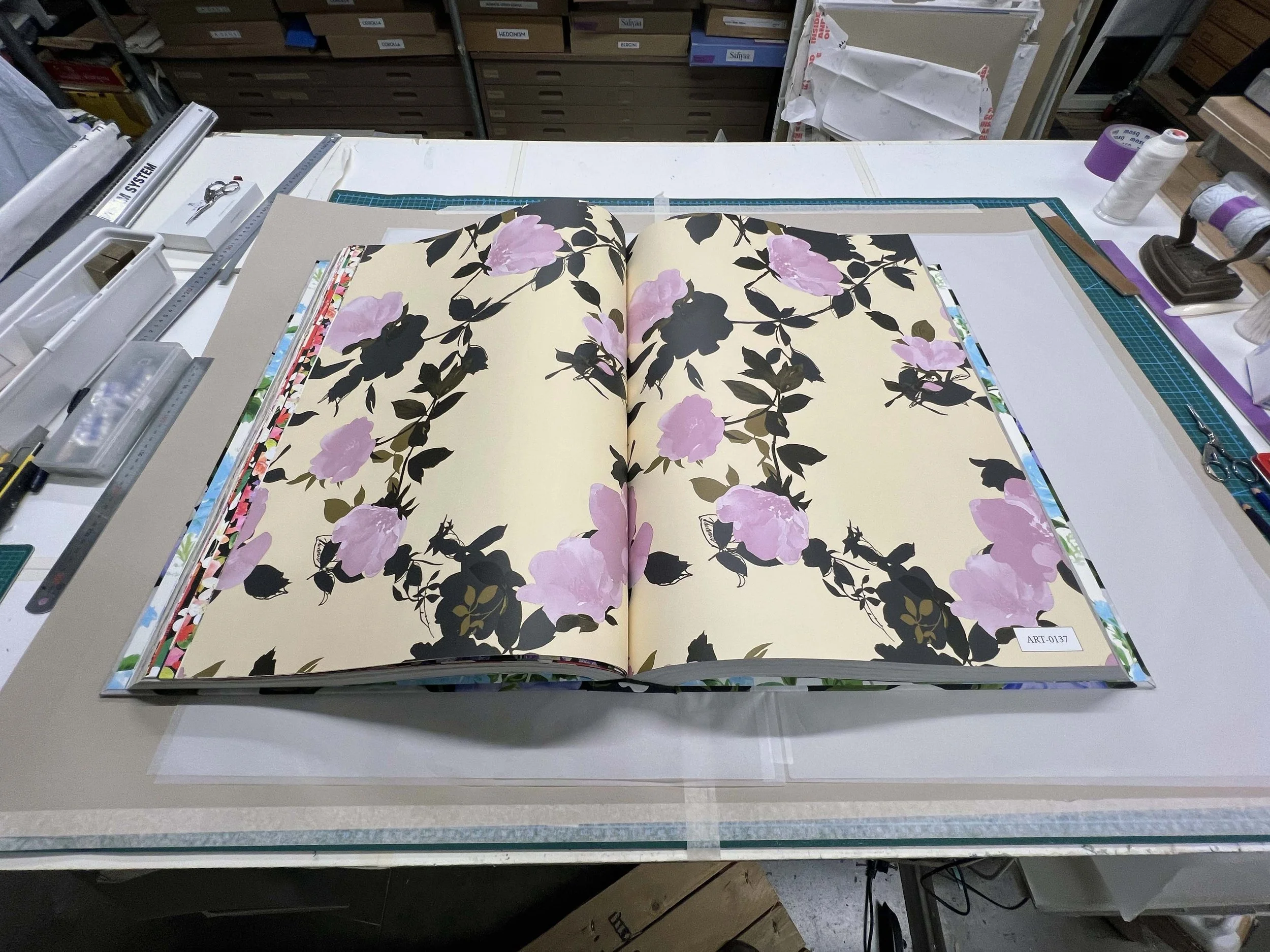

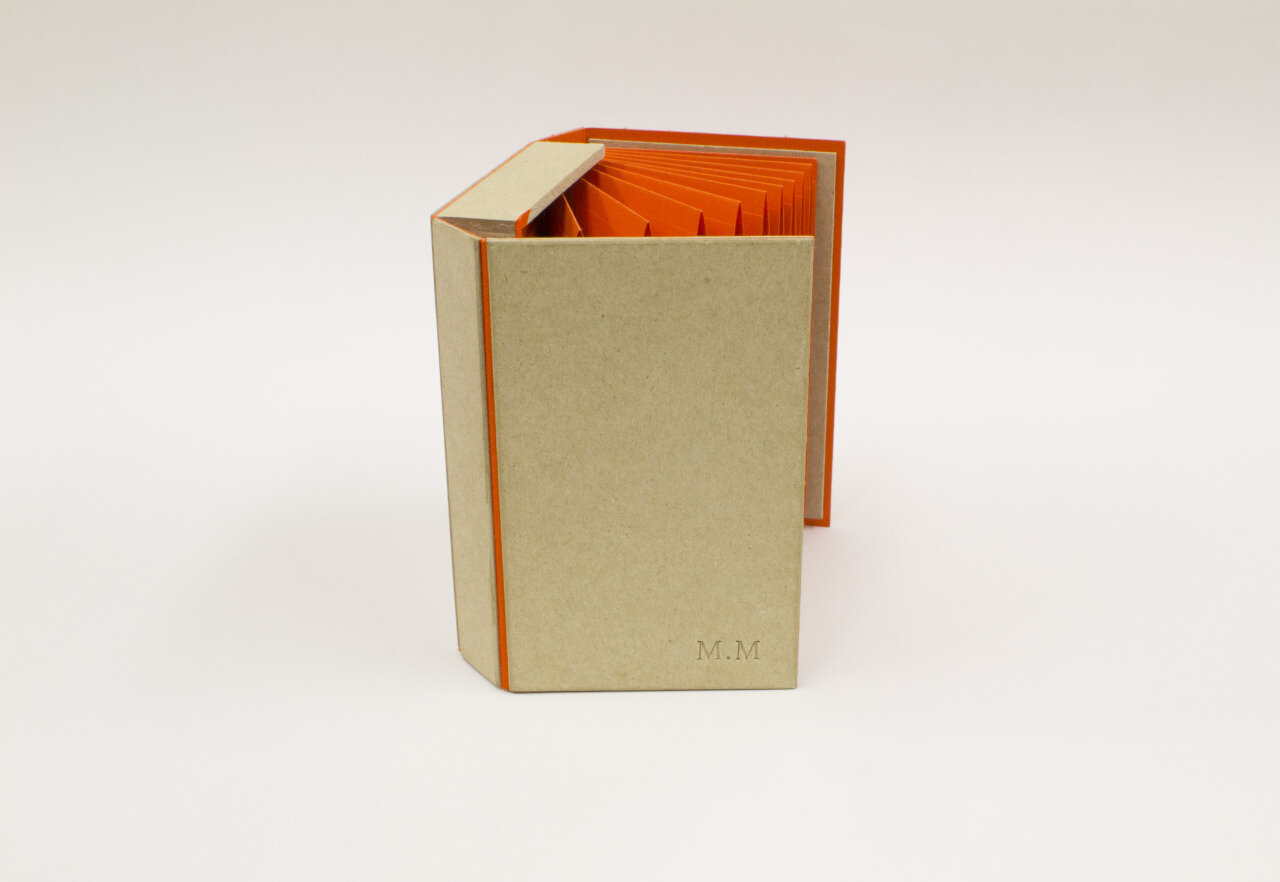

The Ephea Book

Ephea gave me an open brief. Not an object, but a manifesto of materiality: something to slow us down and reawaken the senses. Before decisions or meaning comes feeling; it leads intuition.

From my piece in the Ephea Journal:

“When I first envisioned the Ephea Book, I thought about creating something far beyond a simple sample collection. I wanted to create an object that would function like an archive, but feel like a gallery, a space where each element had time and room to tell its own story.

I drew inspiration from vinyl records’ cases, yet I reimagined their structure to frame each sample as a unique material narrative. Every sheet of Ephea carries its own expression: textures, tones, densities unfolding one after another, designed to be explored slowly, by hand, with presence.

I wanted the structure to guide the journey, to decelerate it.

Not just a swatch book to flip through, but an instrument of discovery: tactile, intuitive, crafted to invite care and curiosity. Each gesture becomes a moment of encounter with the material, a silent dialogue between fingers and paper.

This is what makes the Ephea Book unique: it transforms consultation into experience, samples into stories, choices into discoveries.”

Question: are you familiar with Ephea's mycelium based materials?

Take a look here.

P.S. I’ve collaborated with Ephea and Mogu (Ephea’s sister company for architectural materials) for some time, and the evolution of their materials has been remarkable. Here is an interview in The New Bookbinder, Vol. 40 (2020), where I tested their early materials.

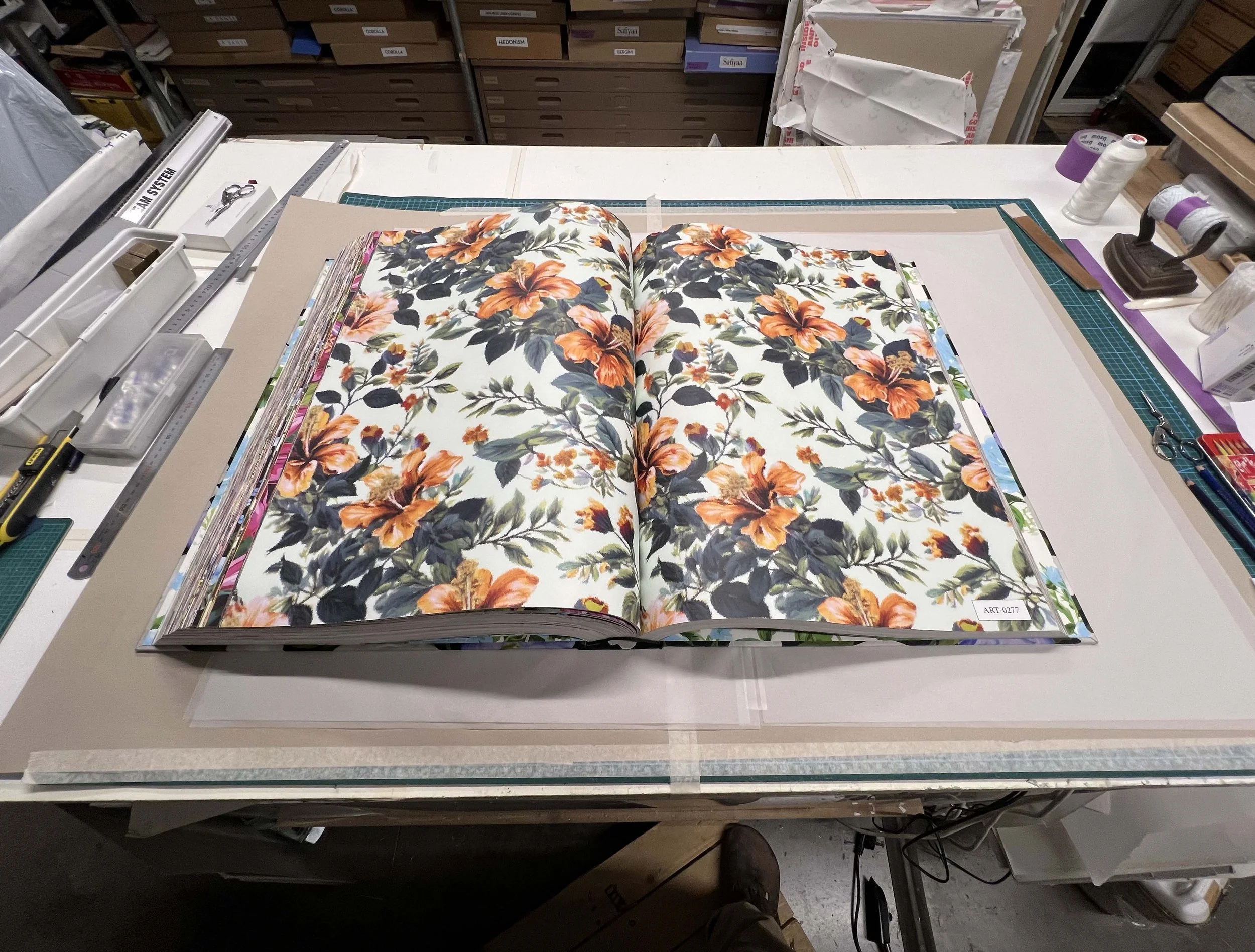

On cheating gravity

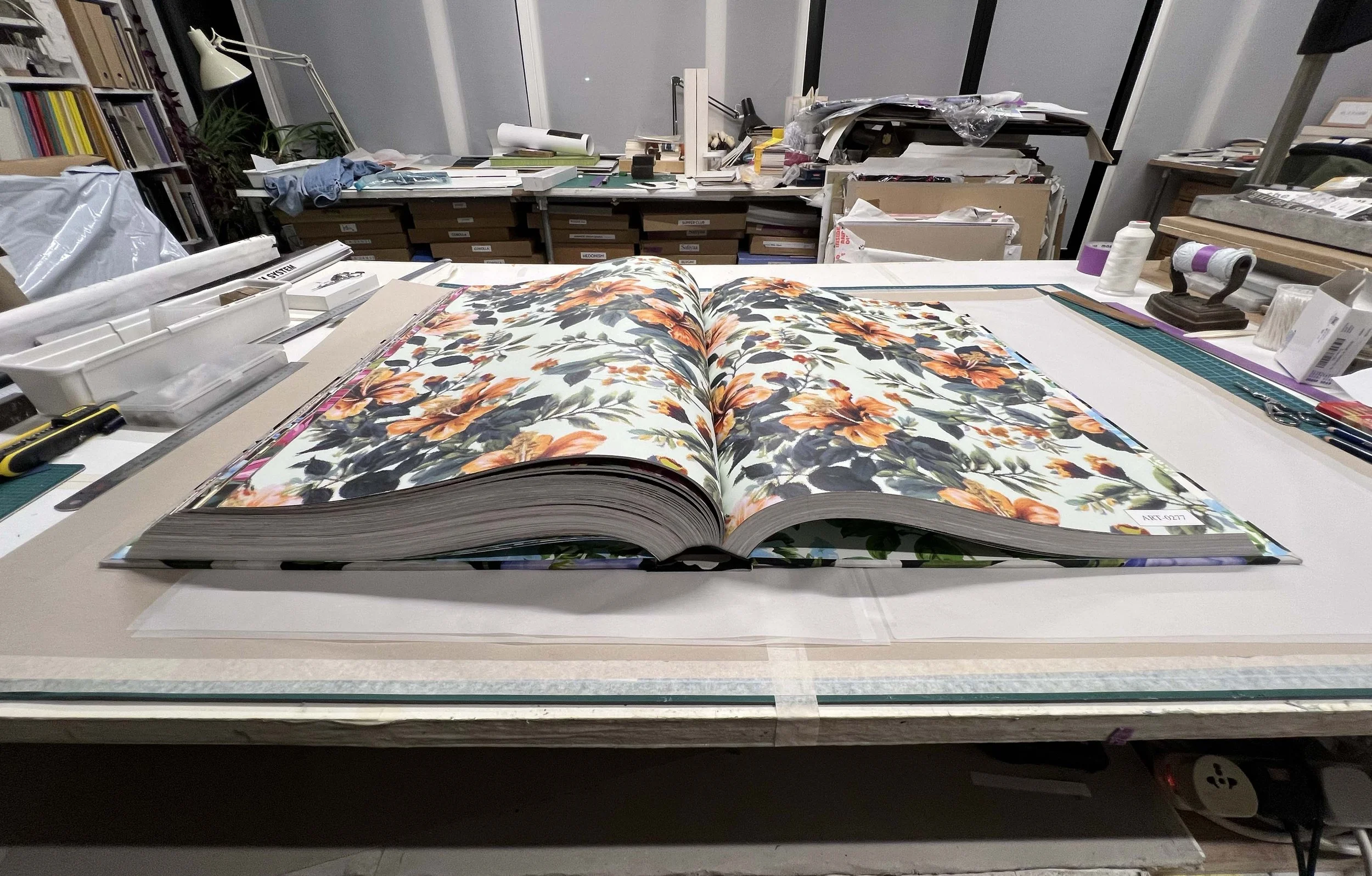

Last weekend I bound an A2 portrait book (420 × 594 mm), about 800 pages, almost 20 kg.

One of those commissions with an insane turnaround: if anything slips, you fix it on the fly and race the clock.

People imagine a bookbinding studio as a relaxing space.

The reality, especially in a big city like London, working to fashion and communications agency timelines, is the complete opposite.

We planned six working days. Files arrived two days late.

Then the printing press went down, twelve hours lost, and the first run arrived with issues that needed reprinting; another day gone.

2.5 days left. What do you do? You decide it’s personal. You make it happen.

I delivered at midnight on Sunday. I always swear I won’t take these jobs again. But there’s something powerful about making to the highest standard within a tiny window: a kind of total focus that turns down the noise.

When it’s finally done, it feels like cheating gravity for a moment.

P.S. Special thanks to Simon and Ira at LCBA; Nicky Oliver of Black Fox Bindery; and Francesco of Studio Bergini.

Lesson from la Tourette

Some buildings you simply visit. Others seem to visit you, shaping your thoughts, slowing your pace, and leaving an imprint that lasts long after you’ve gone.

In mid-July, while driving from London to Marseille, I had the pleasure of staying one night at Sainte Marie de la Tourette, a monastery near Lyon and the final building designed by Le Corbusier.

What struck me most was how light becomes an active participant in the architecture. It doesn’t simply illuminate; it moves freely, sliding across walls and floors, inviting you to follow.

The building uses undulating glass panes to control the light entering its large public spaces and long corridors, creating a rhythm of shadow and brightness that changes throughout the day.

With so little else competing, mind settles. Focus arrives. Attention deepens.

It’s a powerful reminder that inspiration doesn’t require abundance; the minimum, handled precisely, is enough.

Do you rearrange your space to think better, or let the space arrange you?

I’m exploring how studio layout affects error rate and flow.

If you have any tips, I’d love to compare notes.

P.S. The last picture shows my favourite architectural detail: the “sugar cubes.” They are everywhere. They serve no structural purpose; they’re there to frame the view, compelling you to focus more intently on what’s in front of you. Genius.

MAZZOTTI BOOKS' Manifesto

At the end of March last year, I attended an unforgettable workshop in London organised by the DO Lectures and run by David Hieatt and Mike Coulter. The focus? How to write a manifesto.

A manifesto is more than a set of rules or aspirations; it’s a compass. It’s what you return to when decisions get tough, when the path isn’t clear, or when you need to remind yourself why you started in the first place.

It’s taken me almost a year and a half to distill my ideas, challenge my assumptions, and put the words in the right order. But today, I’m happy to share the outcome, the foundation of what Mazzotti Books stands for and where it’s heading.

At Mazzotti Books,

We believe in the transformative power of books

Every book we create embodies our passion for curiosity and imaginative thinking, helping to shape a future where diverse ideas and perspectives are celebrated and treasured.

We are committed to those who care

The individuals and brands that dare to think bigger and strive for quality and individuality.

We uphold a standard of excellence and purpose

Ensuring that every decision we make reflects the integrity of the project and the creativity that defines us.

We thrive on challenges

Every day we receive ideas that no one else has been able to give shape to. We see them as opportunities to discover and play.

The approach is as important as the outcome

Creating a book is a multilayered process of navigating and discovering physical nuances.

We take you on a journey.

Craft matters

Craftsmanship infuses our work with meaning.

We care about our craft and the people we do it with.

We don’t just produce books, we breathe new dimensions into stories

Through form, structure and materials, we recontextualise narratives.

Daily Practice

A different way to approach thinking and making

The idea was born from a peculiar Instagram phenomenon in which makers feels the urge to post at least one picture of their paper offcuts, sharing their innate beauty and incredible potential, but rarely exploring it further. As Martina Margetts[1] wrote:

“Today’s internet deprives us of a connection with things: obsessed by surfing images, we consume superficially and judge prejudicially.” [2]

It is not enough for me to make useful objects. My aim as a bookbinder, artist and maker is to understand, deconstruct and reveal the physical nuances of my favourite medium: the book.

I started to collect offcuts because I felt that some of them were much more than merely the residues of processes. The simple act of accumulation led me to see them as a new raw material to be explored and used in different ways.

At the same time, I was inspired by Gongshi – spirit stones (popularly mistranslated as Scholar’s Rocks in English) after I worked on the seminal publication Crags and Ravines Make a Marvellous View published by Sylph Edition. In China, in the middle period of the Tang dynasty, during the first half of the 9th century BC, an enthusiasm for rocks developed in Chinese culture which gradually spread to Japan and Korea, and has continued to the modern age.

Rocks are venerated with all the respect that we would accord a work of art; except that what is really being honoured is the power of nature rather than the human hand. In a similar manner I started collecting urban debris from all around my studio, an area with an ever-increasing rate of development. By recasting the construction debris, I detached them from their past and gave them a new life, a new perspective through which to be seen. The appreciation of these objects, being man-made, becomes a starting point for reflecting on the power of creation and destruction contained within human hands.

I crystallised this current idea by creating a series of four new sculptures that explore the complex relationship between process and outcome, utilising the ‘in-between’ materials to capture nuances of the process that are otherwise invisible. At the same time, I wanted to create a departure from the linear narrative of binding a book – an object that itself is inherently linear – by developing a new visual language rooted in its physicality.

Daily Practice is now exhibited at “The Art of the Exceptional’ WOOD-GLASS-PAPER hosted by Fortnum and Mason on the third floor of their Piccadilly store until the 8th of May 2022.

[1] Martina Margetts is a Senior Tutor of Critical and Historical Studies at the Royal College of Art in London. She was Editor of Crafts magazine, and has curated a number of exhibitions for Britian's Crafts Council.

[2] Documents on Contemporary Crafts No.5, Material Perceptions published by Norwegian Crafts Arnoldsche Art Publishers, 2018

Mycelium Books

Interview for The New Bookbinder Vol. 40 - 2020

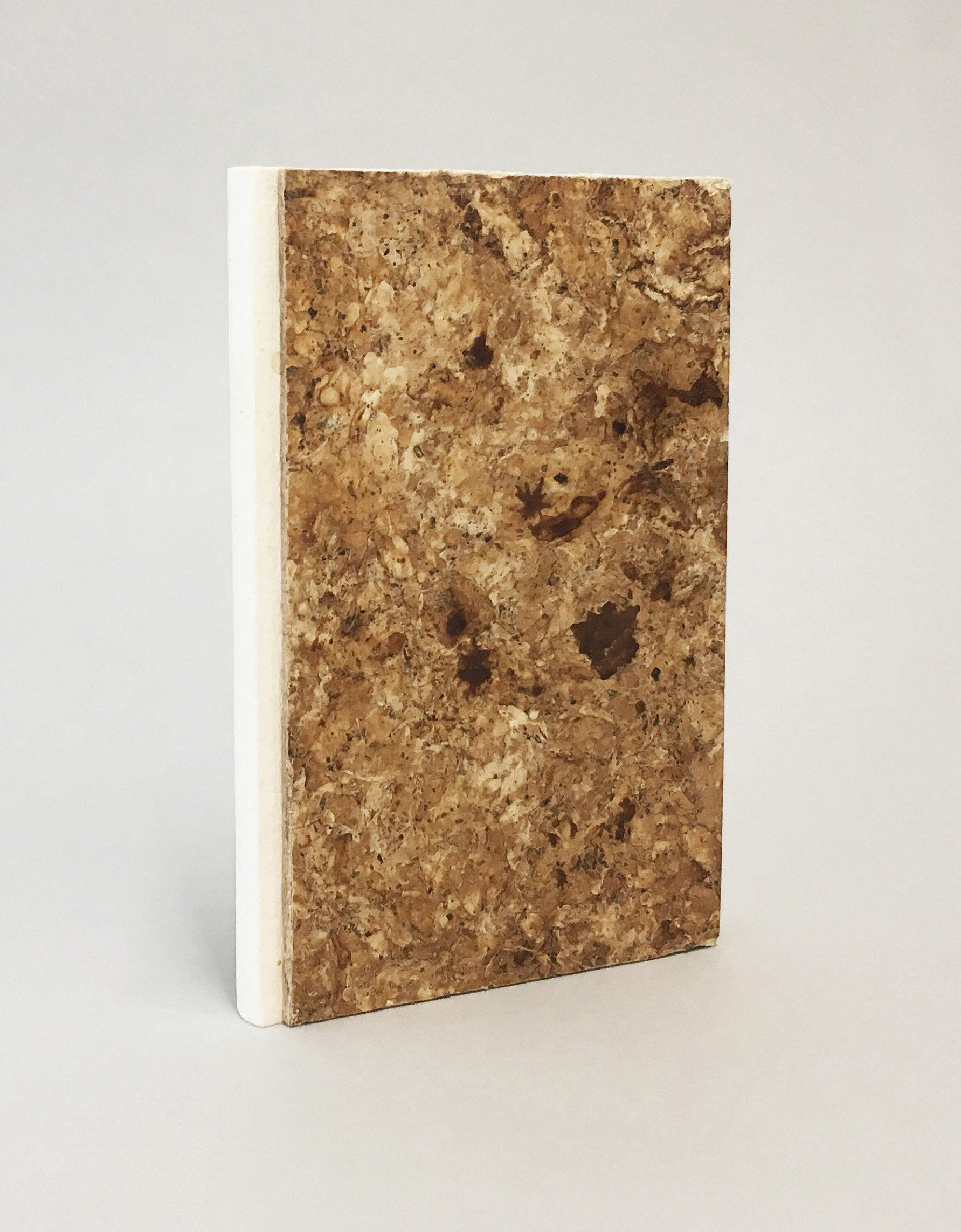

Fig.1

The Mycelium Books are part of "The Growing Lab - Mycelia" collection and are an ongoing exploration into using pure mycelium materials as an alternative to traditional animal leather traditionally used in bookbinding. Experiments in creating and using this material are being carried out by Officina Corpuscolu & Mogu [1] in close collaboration with Mazzotti Books .

What is Mycelium?

Mycelium is the vegetative part of a mushroom, namely the group of micro-organisms that we call fungi. Part of the many fundamental tasks that fungi perform within the natural ecosystem is that they are responsible for breaking down organic material and transforming these into freshly available nutrients that can promote the growth of multiple life forms – for example plants, insects and other microbial life.

How is it made?

Mycelium materials are cultivated by means of fermentation.

By growing fungi on a large variety of substrates deriving from agro-industrial waste such as straws from hemp, flax, wheat, rapeseed as well as wood-chips and sawdust from many wood types, it is possible to create a wide array of materials with different mechanical/technical properties (like tensile strength, compression strength, impact resistance, etc.) suitable for targeting many different applications, both within the creative and industrial world (i.e. furniture, interior design, fashion, etc.)

How is it currently being tested - that is, what products are being created?

Experimentally, Mycelium has been used to create many different products within the building industry, in furniture making, architecture, and the fashion industry but the actual range of products currently available on market is still limited. Mogu is in the process of releasing products for interior architecture and comfort, such as acoustically-absorbent and resilient flooring solutions. The company is also working on finalising flexible materials and solutions suitable for use in the fashion, fashion accessories and automotive industries.

How did Mazzotti Books become involved with Officina Corpuscoli?

I met Maurizio Montalti (Founder of Officina Corpuscoli and co-Founder of MOGU) when we were studying at the University of Bologna, Italy. Since then, besides our personal friendship, we have always been in touch about professional developments, updating each other on whatever we are working on and trying to create opportunities to collaborate on joint projects. In 2016, we decided to create our first three books for an exhibition called Veganism which was staged at Dutch Design Week (Figs 1,2 & 3).The books were produced by using the early prototypes of mycelium materials developed by Officina Corpuscoli.

Since then, the materials have gone through an incredible amount of development and improvement, and Mogu’s new range of flexible, pure mycelium materials (called PURA) was premiered in November as part of Biofabricate 2019, in London.

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

How does the research exchange work?

Officina Corpuscoli and Mogu are growing, testing and developing a variety of materials to be used in other industries and as a bookbinder I consider this an exciting opportunity; to able to work with a new material that has already been subjected to development and testing on other applications and that we feel could also be used for bookbinding.

Once a suitable material has been selected, I receive a sample and start handling the material, feeling it and understanding its properties.

I usually start by creating a case binding, just to see what the material does and how it reacts to glue and foil blocking. After that, I assess it and report back. This feedback loop continues until we have identified the most promising solutions.

Describe the material - what does it feel like? What is it like to work with?

The Mycelium I used as board material in book 1 (Fig.1), in 2016, has a lightweight consistency with a cotton-like feeling along the edges. In order to contain the fluffiness along the edges I have applied a thin layer of EVA along them. Unfortunately, although having a very interesting texture, it is not as resistant as millboard or grey board (it doesn’t bend, instead it breaks) and at the moment it only comes in a few thicknesses; the thinnest being 3mm. (Fig. 4 )

Fig. 4

On book 2 (Fig. 2) I used a leather-like material similar to Amadou [2], a material derived from fomes fomentarius [3] and similar fungi that grow on the bark of coniferous and angiosperm trees. To the touch it is very similar to suede, but much thicker and more spongy. I used this material as panels for the front and back covers, just gluing it on top of a 1mm millboard board with no turn-ins. To press it I used some thick memory foam between the pressing boards and the cover. The visibly darker areas are where there was either more pressure due to unevenness of the material or more glue. Like suede, it doesn’t take foil blocking very well.

On book 3 (Fig. 3), I created a central panel on the front and back cover with a different material closer to latex rather than leather but far less stretchy. This time I did turn-in although the material is almost impossible to pare, with different thicknesses throughout. The result is uneven turn-ins. Apart from this issue the texture is very beautiful, almost alien and has a noticeable caramel smell. It is also possible to foil block although not easy due to the heavy texture (Fig 5 ).

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

On books 4 and 5 (Figs 6 and 8), I utilised PURA material backed with Fray-not using EVA-con R glue (Fig.9 and 10).

Fig. 9

Fig. 10

The difference between books 4 (Fig. 6) and 5 (Fig. 8) is that book 4 hasn’t been pressed under a nipping press, therefore the texture of the material has remained very soft, so much so, that even after a day of resting under a weight I could still impress a finger print on the front cover (Fig. 7). Pressing book 5 with a nipping press has allowed the substrate backing to come to the forefront, resulting in little bumps all over the cover (Fig. 8).

Fig. 11

Fig. 12

Book 6 (Fig. 11) has been bound with pre-thermo backed PURA (Fig. 12). The material seems very strong and versatile although a bit too thick, around 0.65 mm

PURA materials can be blind embossed and debossed at low temperature, around 130 degree Celsius, but unfortunately it can’t be foiled (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13

Overall, compared to the early material samples that I received back in 2016, PURA materials appear certainly to be more homogenous in texture, density and overall consistency and much closer to a fully viable alternative to traditional animal leather, though not yet fully comparable to it.

Because these materials originate from a fungal skin, they constitute an entirely new category of materials. At the moment, PURA materials are going through major improvements that will possibly allow them to be employed as effective alternatives to traditional animal leather, without any need to be lined with other materials.

What I can see is that there is perhaps a good overlap between what is required by the fashion industry and bookbinding materials which could potentially accelerate the development of new bookbinding materials to work with as alternatives to traditional options.

Can you manipulate PURA like traditional leather?

PURA materials behave more like a book cloth rather than leather.

The materials that I received so far are still under a process of continuous improvement and they stretch relatively little when compared to animal leather due to the back lining.

Having said that, I am aware that there are already new PURA versions without any lining and with major improvements on mechanical properties. This result has been achieved by identifying suitable classical tanning processes.

Generally speaking, I don’t think it is correct to compare this material to leather or think that leather will be completely replaced by it. Soon this new material will have the same performance of leather but with different tactile properties creating a completely new range of materials.

Will it last - what does it wear like?

The first books produced (2016), are now three and half years old.

Book 2 (Fig. 2), unfortunately, has been eaten by flies although it was stored in a sealed box. The material had a high level of sugar content, making it irresistible to them (Fig. 14).

Fig. 14

The other mycelium materials utilised in 2016 do not seem affected or spoiled yet, but I also think that it is perhaps still too early to evaluate the aging process.

The newest book made with PURA lined with Fray-not unfortunately appears relatively fragile. After a few days of handling the corners are damaged and the material has started to delaminate (Fig. 15 and 16). However, the book bound with pre-backed PURA seems to be much stronger and I am absolutely excited to keep following its evolution and observing how it will age.

Fig. 15

Fig. 16

Do you think there is a future for Mycelium as a bookbinding material?

Definitely. I personally don’t use much leather in my work, although I like it as a material, purely because I don’t think leather is always the most appropriate material to bind a book.

Leather is very durable, has a nice smell that we consider warm and familiar, and feels nice to handle. It adds a luxurious feeling, but sometimes it also true that when a book is bound in leather, it often becomes more of a precious object and less likely to be touched, let alone read!

Also, if the book is to continue to be seen as an object that enhances thinking, openness, reflection and imagination; an object that is a reflection of its contemporaneity, then today, perhaps it is becoming increasingly difficult to justify wrapping a book in the skin of a dead animal.

I truly believe that books still have the power to spark curiosity, reflection, and action and at the same time I feel that we are entering an age where material consciousness is not only related to luxury but becomes a necessity that requires a radical shift toward the way we think about materials, especially how they are produced.

If the covering material of a bound book can tell us something about our social history and can comment on our past and current preoccupations, both cultural and political, then definitely bio-based, responsible materials should become one of the first choices to think about when binding a book.

Any ongoing plans?

At the moment I am hosting a writer in residence with the intention to explore the possibility that we don't need books as a medium to share stories. The main questions that we are trying to answer are:

What other ways are there to tell stories? What can a bookbinder and a writer do together that they couldn't do separately? What can collaboration reveal?

Through making books together we will try to understand and find out what physicality means. We will be publishing everything we are thinking about: stories, research and interviews; the only goal being to explore the written word, the internet and books, and to question how we can find new ways to tell stories beyond the physical book.

In addition to this research, over the last couple of years I have been developing a new body of artwork that explores the visual and tactile language rooted in the materials and processes of bookbinding.

As part of this artistic research practice, I mainly focus on the manipulation and grouping of discarded materials, and, in opposition to bookbinding, where everything is strictly controlled and focused toward a specific outcome, I chose my artistic research practice to be free from end goals. I am aiming to present this body of work for the first time by the end of the year.

Last but not least, I am really looking forward to receiving the latest development of PURA materials, without any lining, to test it.

I am quite confident that in the next couple of years, maybe even less, mycelium based materials will be a solid bookbinding option.

If you would like to know more, please do not hesitate to get in touch.

Notes

Officina Corpuscoli (corpuscoli.com)

Officina Corpuscoli (est.2010, in Amsterdam - NL), operates as a trans-disciplinary studio investigating and reflecting upon contemporary (material) culture, through the development of tangibly novel opportunities and advanced visions for the (creative) industry and for the broader social spectrum. Working at the junction between design, art, biotech and ecology, the studio develops design research, curatorial projects, critical installations, technologies and products, often inspired by and in collaboration with living microbial systems.

What do we see when we imagine? What do we see when we read?

by Writer in Residence Sean Russell.

6 min read

I see it very clearly. It is night outside and the cabin is surrounded by trees and the wind blows and rustles the leaves. Inside, sat on the floor, is a young man and a woman in her thirties. The interior is oak and there’s a fireplace and the pair are sat on a white rug and leaning against a grey sofa. She has a guitar and sings a song as he watches, lost in his own thoughts.

This is an image I can see very clearly in my mind. It is an image from the novel Norwegian Wood by Haruki Murakami, and the song the female character, Reiko, sings is of course the song Norwegian Wood by The Beatles.

Honestly, I have no idea if this imagining is accurate to the book. I can't remember anymore. It’s been a few years since I read the novel the point is, I can see that image, it sticks with me.

If I were of the mind, one evening, I am sure I could simply sit there and delve deeper into this image and I would be able to tell you what she’s wearing (a grey sweatshirt and tracksuit bottoms) or the posture of his body (back against the sofa, knees bent, elbows rested on knees, hands lightly touching one another in the middle). The point is, I see it as if it were one of my own memories, as if it happened to me.

Yes, I suppose in many ways it did happen to me. I was there. A voyeur, an eavesdropper, a stalker. Because reading a book isn’t passive like watching a film, instead you are really there, these images are conjured in your mind, and the memories they create become, to me at least, indistinguishable in quality from a memory of my own life.

I see Watanabe and Reiko as clearly as I see my brother and sister, mother and father on a Christmas day morning when I was a child. Can I say the same of films?

I can imagine a film, but what I imagine was not created by me, I was passive. I can recall Marlon Brando with an orange quarter in his mouth chasing his grandchild through the orchard. But it feels like recalling facts, I don't feel I was somehow in the orchard with them. The Godfather is one of the finest pieces of art, that is not to detract from film, it is just to say it is different to reading.

This image conjuring is something I took for granted. A few words on a page and I see it all:

"A red car roars down a road past the bustling crowd."

What do you see?

Do you see anything, or do you simply know what those words mean?

I see it. Not in the sense that I stop seeing through my eyes momentarily, but moments after I have read it, I remember the image as if I had really seen it with my eyes.

I assumed everyone saw their imaginations in the same way. So stupid to assume anything, but I did. I can sit and daydream for hours, but I do not daydream in words, but images, dialogues, entire worlds, parallel universes where I go and speak to the interesting person by the bar instead of standing by, quietly alone.

I see myself in the future, I imagine the past if I had done something different. I see it all, every detail.

Speaking with two friends recently I found out that when they read, they do not see these images. That the people in their books are blurs, faceless, abstract hints of colour and shape. They are no less moved by the writing, and feel everything perhaps just as I do. They just do not see it. They would not see Reiko, they would see no cabin, no trees.

This got me thinking about how one would write for different imaginations. Even if we just take two camps of imagination: those that see, and those that do not (and it is quite possible there are many levels on the spectrum of imagination) you could write two different passages to achieve different thing.

As someone who sees, I love deeply detailed writing. Someone like Hemingway who would write something along the lines of:

And we walked up the hill and the grass was wet from the morning's dew and when we got to the top of the hill we could see out over the trees and in the distance was a lake and the sun shone on us and it was a fine day to hunt.

I can see everything and it’s no coincidence that Hemingway's books stick with me far more as memories than other books, I can say the same of Charles Dickens and Arhundati Roy. Different styles, I know, but swathed in detail.

But take someone like Eimear McBride – whose writing is abstractly beautiful – you may get something like:

A step. Mud. I hope that. Deep breath. We get to the top soon. Oh and the land stretching and swirling shimmering dancing. He, next to me. I, catching my breath. Water down my throat. Look at the lake.

While I think there is something wonderful about McBride's language – read her, not my imitation – to me, personally, it is laborious. I need an image or else I lose interest, I am distracted. The story is reduced to pretty words and I am very aware I am reading, I am inside no one’s world. Whereas I know some friends who deeply love her style and feel everything her characters feel and are entwined with the nuances that can be expressed in this staccato almost private-feeling style. These friends mostly say that they do not see.

There is a term for mind-blindness, the inability to imagine a picture, it is congenital aphantasia. For these people when asked to recall a memory – or perhaps a story from a book – they often describe them as a conceptual list of things that occurred rather than how I would, like a movie reel playing in my mind’s eye.

In an excellent Conversation article the authors refer to Firefox internet browser inventor, Blake Ross, who explained his own mind-blindness in a Facebook post.

“He can ruminate on the ‘concept’ of a beach,” writes Rebecca Keogh and Joel Pearson. “He knows there’s sand and water and other facts about beaches. But he can’t conjure up beaches he’s visited in his mind, nor does he have any capacity to create a mental image of a beach.”

To find out whether the difference was indeed in the ability to imagine an image, and not, just the ability of the person to describe what they see, the authors carried out a study using an objective means to identify the ability of one’s imagination. It is described well in the article, but the result is that it is true that some people just do not have visual imagery.

I wonder if this is a spectrum along which all of us will fit. Those that can see Reiko and Watanabe in full detail, those that see faint images with no faces, and those that can simply process the words and know what they mean with little or no image at all, and everything in between.

Well, then, the way a writer writes a story would affect different people’s experiences very much.

But what about the way a person reads? When we spoke with Jonathan Harris he spoke of reading as an activity in which you are present with just yourself and the book and your imagination, the page. When looking at a screen you are in fact looking into a multi-dimensional portal of the internet, distracted by browsing, social media, email and all that goes with it.

How does that effect imagination? With a book it’s hard to get distracted, with a screen, much easier, so perhaps it is harder to form those images, whatever those might be to you, and even harder to maintain them when your mind wonders so easily off the words and to the red notification; as your hands anticipate the buzz of a new message.

It’s worth thinking about, there must be some reason a book feels different to a screen.

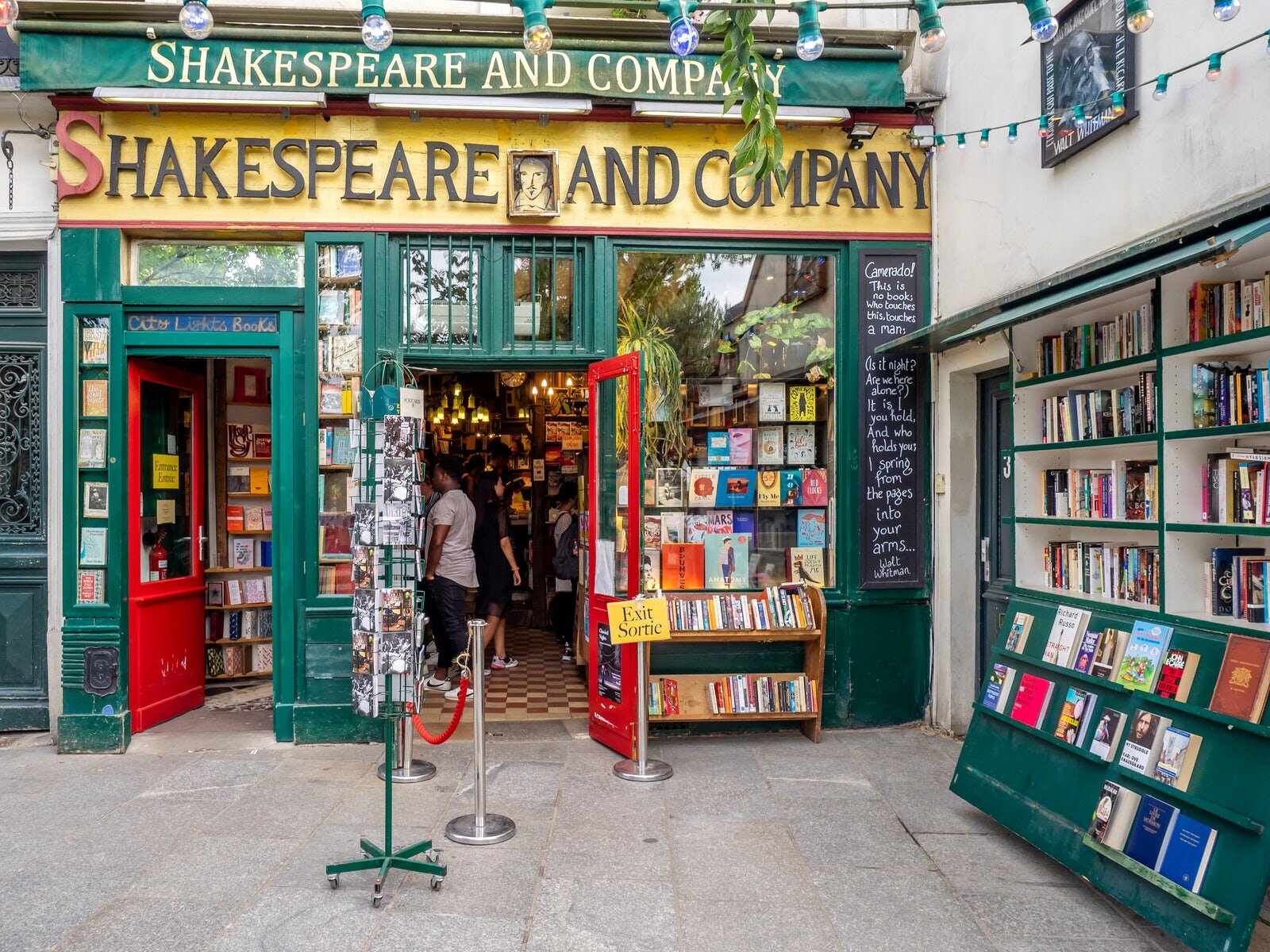

A reflection on my time at Shakespeare & Company in Paris

Writer in Residence Sean Russell writes about his time in Paris based at the literary hub of Shakespeare & Company, a shop that now needs help to survive during this pandemic.

When I arrived in Paris it was cold and it was January and it was grey and the wind blew. Yet somehow the city always has a beauty that others just do not have, whatever the weather may be. It was 2015 and I was 22 and idolised Hemingway amongst many others and saw no other place to be other than Paris, I saw no other place than Shakespeare & Company.

I didn’t have a lot of money but had discovered that if you thought of yourself as a writer you could live in the shop so long as you worked there for two hours a day and helped open and close it. You also had to write a one-page autobiography at the end of your time there and traditionally you were supposed to read a book a day – although I can’t say I managed quite that rate... These were George Whitman’s rules for letting people stay in his shop on the Seine looking directly at Notre Dame, rules which still exist to this day under his daughter, owner Sylvia Whitman.

I could think of no better place to be, Shakespeare and Company is more than a bookshop, it is a history and tradition. Many writers have passed through its doors – including the likes of Allen Ginsberg and Gregory Corso – and many famous people have come and gone. I remember meeting Owen Wilson in the library there, sitting down to enjoy a book one quiet windy evening.

The shop was so busy in the day, hundreds of people crammed into the place in a way that is unimaginable now during the pandemic. One of the jobs I would do during my two hours was stand on the door letting people in and out as queues built up to see this wonderful little nook in Paris. The customers would ask for book recommendations of us and we would happily give them and on some evenings, authors would read from their works to a wine-drinking audience.

But for the tumbleweeds – the name given to the writers who sleep in the shop – it was when the customers left that there was a different kind of magic. When night came, and the final readers and shoppers were gone, we would close the doors and be surrounded by quiet and books. So much more the quiet after such a busy day.

We would stay up drinking wine and reading books and chatting and writing, I made some of the very best friends I ever made in the shop and felt like I was part of this great tradition. Up on the third floor of the building there was an archive of one-page biographies, thousands of them dating back decades. We used to go through them and read them and find that we were just part of this long line of people looking for a Parisian dream. My autobiography, if I recall correctly, was horrifically pretentious.

The shop acted as a hub, it was where people were drawn not just from all over the city but all over the world. All small independent bookshops are important to the communities that love them, Shakespeare & Company’s community just happened to be from everywhere.

Some of the most cherished books I own are the ones I got from Shakespeare & Company with the little stamp inside the front cover reminding me of some little memory of the few months I spent in Paris sleeping next to the piano upstairs, but also after I left the shop and returned to meet friends and buy books.

Like many independent shops around the world, Shakespeare & Company is struggling in the pandemic and for all of us that love the shop it’s time to help if we can as they push for support. Any book from Shakespeare & Company is to be cherished by all book lovers, you buy into the heritage of the shop, you buy into the idea.

Now, if you can, please help support this wonderful shop. But if not Shakespeare & Company then any of the other independents needing help to survive right now.

Support Shakespeare & Company here.

A change of perspective

by Writer in Residence Sean Russell.

I felt I had to leave the UK and London for many reasons. First among them was that I could. With the switch to working remotely the whole world became my office. It took a friend to make me realise this, but once I began to think about the possibility of what I thought would be impossible in March – I decided to go to Palermo, Sicily.

While the first reason was that I could leave, the next reason was a feeling of being exhausted with the country. Tired of the outrage and anger; the divides so clear. Tired of the city. Samuel Johnson said if you’re tired of London you’re tired of life. Samuel Johnson probably never paid £700 for a room in a shared flat in the middle of a pandemic where all of those great things that make the rent worth it are closed.

I longed for the countryside and quiet, I longed to be alone. I longed to change my perspective.

As a writer there is perhaps little better you can do than change perspective. When you are so comfortable in the place where you are, the people you have around you, your routine, what can you possible write about? Or more importantly than “what” is how can you be sure of anything you write when you haven’t seen anything else? When you have nothing to compare and contrast.

Italy fascinates me for the obvious reasons – the food, the scenery, the architecture. But I also love the cinema, the cycling, the history. I wanted to learn Italian, a language which prefers a beautiful way to say something over a functional phrase – there are at least 10 words for “the”. And so I decided to go to Sicily, just to see how it was, to change my perspective. It was, as Jonathan Harris might say, “the next clear thing” for me at the time.

And so I left.

Accompanying my arrival in Palermo came a peace in solitude. I began to think clearer about my own little personal problems and saw that really they were not problems at all, mostly – not in the sense of real problems. I saw that everything in my life was good or as good as could be in a global pandemic, and I am lucky and grateful. I saw that people were outraged in the UK because they are exasperated, because the country that once I was so proud of is an embarrassing mess. I understood that they knew no other way to express this than in anger and outrage on social media.

To me Italy has always been an idea, a fantasy of mine. I had images of Jude Law in The Talented Mr. Ripley in my head. La Dolce Vita – I saw myself sitting over an espresso with La Gazzetta Dello Sport, wearing a suit and looking over my sunglasses like Marcello Mastroianni in 8 ½. But the fact is, as with most fantasies, the truth wasn’t there, at least not in Palermo in the middle of coronavirus.

One of the issues of travelling during a pandemic is a constant feeling of anxiety. You’re not entirely sure what’s going on around you, but everyone is keeping to themselves. And that’s a hard place to be when you’re alone. I’ve never much found travelling alone hard, but in a pandemic it takes the confidence right from underneath you.

But I did travel to Solunto, lauded as Sicily’s Pompeii, and it was empty because there are few tourists at the moment and I took the train out and walked up hill for 35 minutes in Birkenstocks because I believed erroneously that it was a five minute walk. And there I had a Phoenician/Greco/Roman settlement to myself. I walked around and imagined mundane scenes because really people haven’t changed all that much and probably were complaining about such and such a pain in their back and how hot it was or something. I found a room in a ruined old house which said it was the toilet. Now, the toilet to me is a great thinking place, and so I thought it must have been for someone long before me. So I sat on the “toilet” and did my thinking where once someone else did their thinking, and it was comforting to be able to meditate in this way in this place.

I'm not sure I could live in Italy, but I could spend time here, I could get away from the UK and breathe and ride my bike into the mountains which is perhaps one of the finest experiences I have ever had in my life here in Palermo, and I could do that every year for the rest of my life and that would be a happy life.

But while here I also began to think about pub culture, I don't really know why, except that I love British pub culture. There’s something about those stale-beer smelling places of friendship. I realised little things, like in the UK most everything just tends to work, whereas in Palermo I just assumed they wouldn't and was happy when they did.

This is not a love letter to the UK. I am distressed by the state of the country and its government. I am embarrassed where once I was never embarrassed. And I cannot get over the odd obsession with World War 2. But good or bad the change of perspective helped me think clearer.

Whilst here, I began to experiment with other forms of writing also. Here in Italy you cannot help but think of beautiful things when surrounded by them all the time.

Haiku (the modern kind as opposed to the pre-modern style) is something I have never played with. It never really made sense to me. But being here and trying to see things differently there is something about those 17 syllables that forces you to see things for what they are with no imposed judgement. The symbolism is suggested, the idea is hinted at, but ultimately, they are all about the same thing, the moment, and the impermanence of all things.

Being confined to 5-7-5 makes me think and see things differently and I hope to continue writing Haiku when I return to the UK and beyond. How better than to capture a moment? To change one’s perspective?

There’s a ring of wine

Amongst others on my desk

All of them are mine

A lizard scuttles

Downwards past the balcony

A fly flies away

A blue shirt old man

Puffs his cigarette butt

Over his face mask

A chocolate wrapper

Washes up in the bright sand

A small fish struggles

Salt and pepper man

On the balcony clips his nails

They rain on the street

‘Screens have a disregard for the environment where they live, whereas books are part of that environment’

A conversation with Jonathan Harris

(All images belong to Jonathan Harris ©)

12 min read

The Whale Hunt

Crickets chirped constantly and serenely somewhere in Vermont when Jonathan Harris, the award-winning internet artist and designer, joined us on Zoom, it was 11AM there in the countryside. Meanwhile I was in Northamptonshire where the wind lashed the house and rattled the fences and Manuel was in his studio in London.

Jonathan had joined us to discuss his work, work which had captured the imaginations of both myself and Manu and in many ways inspired this residency.

One evening after a few glasses of good wine and good food I was sat on Manu’s sofa in his flat and I mentioned The Whale Hunt. I explained that this was a website like very few I had seen – a beautiful cross between photojournalism and computer-science and data-visualisation and, most importantly for me, human stories. With this website – which presents the Inupiat people of Alaska as they wrestle the leviathan from the sea – you can follow the stories of multiple people through thousands of photos Jonathan took himself, mimicking his heart beat, while living with them for nine days. To me this ripped open the storytelling medium. It did something that books could only dream of doing, being so limited as they are in the physical sense.

Manu was stood up and full of energy and told me it sounded like a project he loved called The Cowbird.

That’s the same guy as The Whale Hunt, I said.

*

I can offer you guys a bit of a preamble about my personal experience with books, said Jonathan. Behind him were white walls and shades of blue furnishings and oak shelves and windows and bookcases and the place seemed quiet. One of the main reasons that I started working with code to begin with was I was robbed at gunpoint. I used to keep very elaborate sketchbooks with water-colour paintings and plants and writing and all this stuff, they were really tactile, beautiful objects and I would bind them by hand, and then I had this robbery happen while travelling in central America and I got beaten up pretty badly, I had a gun put to my head and my sketchbook was stolen along with a lot of my other things.

I had been studying computer science in college, he continued. But I hadn't used it as an art medium yet and I thought: I'm tired of making things that can be stolen, like a book, so I'm going to work with code, and no one can steal that. Once it's on the internet it's permanent. Ironically, fast forward 15 years, a lot of the internet technologies that I used to make those early projects are now either obsolete or will become obsolete very soon. So, The Whale Hunt for instance, by the end of 2020 flash will no longer be supported. Basically, those projects will also be stolen, except not by someone with a gun but by corporate policies. So it's just ironic that in a way it kind of started with books and then went away from them and then I realised that actually books are probably the most permanent thing and they can survive through time so well because they don't rely on any technology other than physical matter.

Jonathan has an art background – he paints and creates colourful landscapes and used to keep water-colours in his notebooks. He explained that before the robbery he hadn’t been totally absorbed by computer science yet and although he was taking it as a course requirement at Princeton he hadn’t taken it any further until after the robbery when he realised that with the internet it felt like nobody could steal your work.

He told us about being asked to create a personal homepage while studying and he found that by putting photos of his paintings online he could send the hyperlink around and had a really easy way to share his works. This was a moment he describes as an epiphany.

Nowadays it seems so simple. But at the time it felt revolutionary that there was this way to introduce people to my artwork that didn't require being with them physically. I just felt like, wow, this is going to be such an exciting frontier that's opening up and I'd love to learn about how to create for it.

There were two sides of him – the computer-science side and the art-making side. He resolved to put these together when he received a fellowship at Fabrica in Italy and decided to use computer science as an art medium and created his first project: Wordcount (2003).

Wordcount is a visualisation of the 86,600 most popularly used words in the English language ranked in order. The bigger the word the more it is used and the smaller the word the less it is used. Some of the patterns that emerge are humorous or perhaps insightful. For example, the word “God” is only six words away from “War.”

Listening Post

It was when he came across Listening Post a work by Ben Rubin, a sound artist, and Mark Hansen, a statistician, that Jonathan realised how art and data could really meet.

Listening Post (2001-2) used algorithms to scan internet chat rooms in real-time and take words from them. Then 231 electronic screens in an 11x21 curved wall displayed a word each while a computerised voice reads the words over each other and a monotonous drone fills the air.

That piece got me thinking about mass internet data as an expressive treasure trove of human sentiment and shortly after that I created ‘We Feel Fine’ which was very much inspired by listening post.

This period saw Jonathan create many projects which he now refers to as the early, data-visualisation part of his career. We Feel Fine (2006) scanned internet for uses of the words “I feel” and “I am feeling” to create a dataset of people’s feelings as they expressed them into the void of the internet, which in 2006, was yet to become what it is now and was altogether something more innocent.

We Feel Fine, tried to use data to express something inherently human. Each data point was a person’s feeling and the user could filter down to very specific points by gender, age, weather, location and more. It was this mixing of the macro and the micro levels that Jonathan had wanted to achieve and is perhaps his most unique offering to this art form and medium – the ability to switch between the micro and macro. To be able to go from how an entire country “feels” down to what a girl in her 20s in America feels and back out again. This is what books cannot offer and is perhaps unique to the internet medium.

We Feel Fine

After We Feel Fine followed a period of exploring this unique dynamic. The Whale Hunt (2007) and Cowbird (2011) carried on from this data visualisation and viewer-controlled-filter storytelling. But the problem was he had created something so complex that he wasn’t sure people were using it to its full potential – barely scratching the surface of the micro and the macro.

There was this simple phrase that actually Golan Levin first introduced me to, Jonathan told us. This concept that a good tool should be instantly knowable and infinitely masterable and so he gave the example of a piano and pencil which are things that are instantly knowable – like a four-year-old child can use them – but infinitely masterable. You can spend your whole life trying to master these mediums and still be learning when you die and so with those interfaces that I was designing back then I always wanted them to be instantly knowable and infinitely masterable. They should be self-evident and fun and playful to explore but they should have incredible depth. The downside of that approach is that most people only stay at the instantly knowable part, so there are whole dimensions of these projects that were impeccably thought out and designed that people would never see because people wouldn't find them, or they wouldn’t think to go there.

To Jonathan there was another issue. While he spent years on these projects and won awards for them, he began to feel they just didn’t go as deep as he wanted them to go. He found that the artworks he admired most – be it an Andrei Tarkovsky film or a Bob Dylan or Leonard Cohen song or a poem – touched him in a way that his projects and those of his peers just didn’t. Trying to resolve this led to a period of creative block.

It wasn’t clear to me how the internet medium could be used to go deeper, he said. I wasn't making any new work and I was really confused about what to do next and ultimately in that period I started doing a lot of reading and exploring philosophy and meditation and other states of consciousness and through some experiences I had during that time I had this experience of radically breaking open the frame.

And so from Brooklyn and the bustle of the city where everyone knows what everyone is doing and rushes everywhere and stops and wants to talk and know what you’re doing and is wonderful in its own way, Jonathan moved to his family’s quiet property in Vermont where the crickets chirp.

Today

He began to see life as the canvas and suddenly art was no longer about rectangles, be it a frame or screen. Instead, moulding a life that he was happy in became the work and then what came from that be it videos or paintings or woodwork or websites would be all the better and deeper. He began to follow a new philosophy which he calls “The next clear thing”. By just doing what feels right at any time – be that artistically or in relationships and life – then magic can happen. It was just about being open to experience and turning up.

Slowly, Jonathan returned to website art but this time instead of endlessly open and complex, his newest work – which he is creating now – follows a more linear path which is in some ways more like a book.

So, myself and Manu ventured to ask, as the wind battered my windows, what he thought of physical books. Jonathan was so rooted in storytelling through the internet and produced only one book in his career which ran parallel to We Feel Fine, we wondered what his thoughts were towards storytelling through the codex as opposed to the digital, the unphysical.

I think books are not going to go anywhere, he said. There's a certain amount of simplicity to books. Do books fulfil some unique need that we have as human beings that other mediums don't? I don't know, I haven't really thought about that. It's wonderful just to be next to the fireplace on a cold winter’s day sitting on the sofa reading a book – and sitting there with an iPad is not the same experience at all.

He looks away and thinks.

Maybe another interesting element is there’s a way in which screens are like windows into a different reality because they have motion and they have interaction and so they're like portals into some other space that's not a physical space where you are, your body is somewhere holding a laptop or holding a phone but when you gaze into the phone, you're sort of going into this other place that has its own set of dimension whereas with a book you're still solidly in the same physical reality that your body is in because the page is not changing, it's there in the same way the blanket is there and the apple is there, and so there’s a way in which books coexist with the environments in which they live, that screens do not, screens have a disregard for the environment where they live, whereas books are part of that environment and in fact they add beauty to it.

We had never thought of it in that way. With a screen, be it a phone, a laptop, or tablet you are staring at a screen, yes, but within that screen is an entire world almost an eco-system. You’re aware that you can click somewhere else, go on Twitter when a notification pops up, there are people on there, and it is its own reality. You’re reading a New Yorker article but somewhere you’re aware that the dimensions of what you are looking at are so much deeper that you could drift off onto social media or follow an advert. The internet is its own environment and reading is only one part of that. You are not starting at a flat screen, you’re staring into something so big you can barely comprehend. And with the page of a book? Nothing. You are there and you are with the book and the words.

The Whale Hunt

So why the internet for Jonathan?

The internet is a way to connect with people and connect ideas I'm creating with people. I guess I could also publish books, he laughs. I see the beauty that's possible in the internet even though it's so rare to find it, I feel like most of my experiences with the internet nowadays are very poor.

The internet is a dark place these days and he tells us that what we all call truth is now so mailable and the internet has been at the forefront of this decline. Dark, pessimistic, false stories have spread, and he points to President Donald Trump as fully understanding this new “reality” while the Democrat Party cling on to a noble 20th century mentality of shouting – No, that’s not right, you can’t lie like that. The internet, he believes, needs more light and more beauty.

Jonathan’s view of the internet, he thinks, is probably a little stuck in 2005 – it is a browser and a mouse and that is what informs much of his works. But he hopes that this vision is something that sticks around because artist’s like him have barely scratched the surface.

I remember the early days of pre-Google, pre-Facebook. You would discover things by your friends emailing them to you and it was like you'd stumbled into a secret, like when somebody had found a really beautifully made internet experiment and you went and it was like a secret room you'd been invited into. I felt like a lot of the early projects of mine had that quality also, when people found them they were like “wow this is amazing that you created this” but we've become so bombarded with information now that we've become so numb and desensitised and usually people are selling something like there's usually some motive behind it, it's rare that people just put something up for the beauty of it now. Sometimes, yes, but it's pretty uncommon, I still love that gift and putting things out there in the spirit of a gift.

He continues to work with websites but now the act of creation is wider. The internet is one communication tool of many, but it could be a book, a video, a painting, whatever feels right, whatever is the next clear thing. What is important is doing things in the right order and living a life in which he is happy to live in, living kindly for the planet, those around him and the wider community. He wants to host designers on his land in Vermont and work on bringing some joy back to the internet and tell stories that will be the light magic against the dark. Through reading, philosophy, creating and living, there is an air of peace around Jonathan and our conversation was insightful. When it was over we said our goodbyes and left him with the crickets chirping somewhere in Vermont.

‘Great writing is great writing, regardless of paper’

A reflection on reading and e-books during coronavirus by Writer in Residence Sean Russell.

On March 21, 2020, I tried to buy a book from Broadway Bookshop in Hackney – The Collected Poems of Allen Ginsberg 1947-1997. I felt that if I were to spend some time in isolation the best companion would be Ginsberg, for some reason or other. Lockdown had not yet begun at this point, but some non-essential businesses were forced to close or partially close. Broadway had decided to remain open, except you had to email ahead your order and pay online before picking the book up at the door to the shop. They were also doing book deliveries to those who had to self-isolate. They didn’t have the book in stock, and I would have to isolate without Ginsberg.

To me, and many others, bookshops are essential. As one would go to a pharmacy for paracetamol if one had a headache, one might also want to buy a book to ease the mental strain of living in this so-called new normal in which we find ourselves drifting anxiously through.

However, on March 23 all non-essential businesses, including bookshops had to close. Something had to give, habits would have to change, mine included.

***

I would regard myself as a lover of physical books to the depths of my very soul. I like to collect books, some of which I have no intention of ever reading, others I will read 10 times or more. I like the smell of new books, I like the smell of old books – second-hand books bring me some joys that new could never provide. I like books to line the walls and nooks, and pile high on the floors. It is hard to make a ‘messy’ pile of books, it is always beautiful. There is something to finding a new bookshop that feels like walking into your home that I cannot explain. I never sell my books, I never throw them away. As a writer, I do not dream of my words being on screen but on paper in someone’s hands. Are you really a writer unless it’s on paper somewhere? And yet I have read more digital books since lockdown has begun than ever before.

Why? Well immediacy for one, at some point, early in this strange old lockdown, we were faced with long delivery times, sometimes unknown. On top of that I felt some paranoia about taking in items from the unsanitary outside world into my carefully cultivated germ-free chamber. And there is also a lingering and underlying feeling that in general I should be reading less physical books for environmental reasons (an issue with myriad pros and cons I will no doubt return to at a future time).

Has this changed my reading experience? I don’t think so, in some ways it is more pleasurable, you can read with one hand and highlight sections you like which are organised in a neat little list – although I haven’t yet once looked at this list again. If I didn’t have to buy from Amazon, I often think I’d buy all my novels and non-fiction books on my Kindle, although not art books or suchlike, that somehow defeats the point. I move flat a lot, I go abroad from time to time, heaving around a whole library becomes weary, sometimes it’s nice to read a book without acquiring more stuff. Stuff, stuff, all we have is stuff.

Digital book sales were already on the rise before all this, how many people will think like me and, having decided it was safer and easier to read digital during lockdown, continue that after? After all there are many people without the same qualms with Amazon as I, and then you’re faced with cheap, instantly deliverable books.

What future then? This remains to be seen somewhere out on the horizon. Many lovers of the physical book may have decided to try something new during lockdown and opted for ebooks, many of these will continue to buy at least some of their books digitally. Then which books do you buy digitally and which physical and what will that mean? I don’t believe that physical books will ever go away and their share of the market suggests as such, but our relationship to them may well change. I feel that there will be space only for the prestigious books, the beautiful books on my shelves – the rest may be digital; great writing is great writing, regardless of paper.

That is a strange relationship that I had not thought so much about. Does what I write change if on paper or on screen? My own perception is yes although totally inexplicable, some allusion to a tradition. My heroes all produced books, not blogs. To be a REAL writer you gotta BLEED on the page god damn it – so physical, so grounded. But great writers are all a product of their times, not their heroes’. Perhaps seeking to be in physical magazines, newspapers and hardback books is just a part of what Harold Bloom referred to as The Anxiety of Influence (a book I read in physical form these past weeks).

Audiobooks are also introducing new audiences to reading (is listening to an audiobook reading? If so, what is reading?...). Audibly amongst other services offer the same sanitarily instant service e-books offer, but with the added benefit that you can continue cleaning or doing yoga while you listen.

***

There was a subtle sadness when I received the email from Broadway Bookshop that they didn’t have the Ginsberg I was after. And here lies something wholly interesting at least to me, and I hope to you – I did not download the book on my kindle. I did not even think of it. I wanted those words, by that man, on paper, in my hands and on my shelf. I wanted to rustle through its pages, I wanted to write witty remarks in pencil that would make no sense to me in a year’s time. I wanted to write obscene odes on the window of the skull. There’s something about a book that connects you to the writer, something inexplicable. Having a collection of Ginsberg in my room felt somehow like having Ginsberg himself there, and that’s a feeling I’m not sure digital could ever reproduce. Draw your own conclusions, I have mine.

How many readers had similar lockdown experiences to mine I cannot say but I imagine that after all of this the habits of book readers will have changed. The independent stores will struggle more than ever before and there will be less on our streets as Amazon’s insidious hands reach inside our homes and minds and tighten its grip. People will feel that Amazon was there for us when we needed it after all… Digital books will continue their rise, as will audiobooks. But I have no doubt that the physical book will remain, in fact if only beautiful books are bought physically, then we may well see a lot more gorgeously designed books. And anyway, we’re going to have a lot of lockdown-inspired and written masterpieces to read next year. How will you be reading them?

Why take something inherently digital and make it physical?

‘I don't tend to see the digital and physical as an absolute binary’ – Writer in Residence, Sean Russell spoke to digital artist Dr. Richard Carter about art, poetry, electric literature, algorithms and the importance of creating something physical at the end.

(pic. Richard A Carter)

“The book is the point,” said Richard. “The book is actually what they’re leading up to first and foremost. I mean yes many of these pieces could be done in digital format and I have explored these on a couple of occasions, but I've never really been very satisfied with it. I'm creating a mode of writing, a digitally generated mode of writing which I want to then appear in a codex format, I want it to be something you can hold in your hand and think about and perceive.”

In early February Dr. Richard A Carter, a lecturer in digital media at Roehampton University and a digital artist, spoke at the British Library about his work generating text with algorithms. He presented two works – Waveform and Swipe.

Waveform uses a drone, with a camera attached, to use algorithms to draw a line where the water ends, and the shore begins. This image is then translated into something resembling poetry; short, terse works of four lines generated by that combination of drone, camera, and code.

Waveform (pic. Richard A Carter)

Swipe, uses predictive text and code to create a ‘swipe’ for each word, a glyph based on Google’s glide keyboard. By generating a swipe for each word – the movement a finger would make on the phone – and turning this into calligraphy. Richard is able to hint at another form of writing.

The works are fascinating and raise many questions. Why take something so inherently digital and present it in a physical book? Is it really poetry that the algorithms produce, is it art? And what do algorithms mean for the future of the written word?

“I don't tend to see the digital and physical as an absolute binary,” he said. “Because the digital is physical in so many ways. The nice thing about the book is it gives me an opportunity to really display that code at the same level as the outputs that its making whereas for most digital art, the code that enables it, is buried behind in the black box which is then projecting whatever we are seeing on the screen.”

He said that in creating books, he was trying to create a digital art that was as simple and elegant as what one would see on a canvas or in the pages of a “traditional” book. It was about bringing simplicity back to digital art, an artform which usually has a whole large infrastructure to go along with it.

Here he displays a shortened version of the code followed by the outcomes of the code. You are not bogged down in endless scrolling and more than anything it takes away the mystery of digital art and lays its working clear. How many digital artworks have I seen? How few have I wondered “what’s behind this?”

By bringing simplicity back Richard hopes to then make people think about the technology more closely. By taking something new and putting it in a traditional format we are forced to consider it properly.

Waveform (pic. Richard A Carter)

But is it art?

“I've always had a fascination with literature and poetry in all its forms,” said Richard. “But I've also always had a long-standing interest in experimental literature and poetry; avant-garde, concrete poetry, visual poetry and these texts that push at the boundaries of what we understand writing to be, and how we display and present writing.”

This combined with a love of storytelling in video games and what could be created through this digital medium which perhaps was beyond that of the traditional book. Richard was able to put the two together with electronic literature.

Whether what the code generates is poetry or art does not really matter. It is part of far bigger question. Richard’s work is about creating another tool, something else to explore and push the boundaries of what we think about art, books, and writing.

“With waveform, it's not necessarily meant to be 'this is the new poetry of the 21st century' instead this is an experimental writing practice that is producing text that might remind us to a degree of how poetry works. There are other stories that we can tell here, other ways of seeing and thinking and that algorithms and digital technologies can play their own part, we're taking these tools and using them for our own ends.”

In some ways Richard’s work mirrors our present relationship to writing and hints of the future. Much of the writing we do in our day-to-day lives is predicted by algorithms. Phones guess the next words, email apps suggest us sentences. But we only consider what this means when put into a totally different context, taken out of the phone, the computer, and put into something like a book.

This was the technique used to create the sentence that runs through Swipe. Richard did not create an algorithm to generate the text here, instead he took advantage of what already existed on his phone, just tapping the Google-suggested word over and over again.

The sentence created was then turned into the corresponding glyphs which are presented in the book. This random form of text generation displays once again Richard’s interest in the human and non-human agency and how they interact. Whilst these words may appear random, they are based on algorithms which learned from how he writes. Did Richard see himself in that sentence that was created for him by his own phone?

Swipe (pic. Richard A Carter)

“I don't know whether the ‘future will be a great weekend’ but nevertheless it felt right somehow that it was saying these things; it definitely carried that echo of me and the way I write.”

It’s less clear how these algorithms will affect the way we write to one another. Certainly text messages have affected our communication. Take the earlier days of mobile phones when a whole new language was developed for speed of communication “How R U?” Then as smart phones arrived, full words returned, and emojis were added. The technology we use undoubtedly affects our language use.

“The Google Gmail application on your phone now gives you pre-made sentences. I don't use them because they seem so brutally short, sort of vaguely: ‘yeah, sure, whatever’ and it’s like ‘no, I want to get something of me across in my writing, I don't want to just let the phone give like a three word answer because it feels rude somehow.”

Will algorithms affect our language? Undoubtedly. Will they change longform writing, personal emails, letters, novels, poetry? Less likely.

Richard’s work is about exploration, not necessarily answers. Whether the words in Waveform are poetry, or whether the glyphs in Swipe are art is not what is important. What is important is the exploration of the questions raised by these books. What we can do with this technology to find new ways to tell stories, new ways to write. Just because something starts digitally, doesn’t mean it has to end digitally. By making books Richard makes us consider them beyond just an image on a screen, we see into the “black box”, we are forced to compare them with other forms of art, to poetry; and that is the whole point – to experiment. Just because something isn’t written by a human doesn’t mean we don’t need to consider it, and the process behind it. These are new ways of thinking about writing and storytelling.

You can view more of Richard’s work, and purchase copies of his books here. And follow him on Twitter here.

Follow Mazzotti Books' Writer in Residence with our newsletter and receive all of our posts straight to your inbox here.

Writer in Residence

"It's basically knitting and chatting."

"What do you mean?"

"Like old ladies who meet up and knit and gossip; same thing."

There is a feeling of chaos in Manuel's studio, but everything has its place, and everything is as it should be.

"And from this chatting and making we get structure influenced by writing - writing influenced by structure; physical and not!"

The idea is to explore by opening ourselves up to the possibility that we don't need books. What other ways are there to tell stories? What can a bookbinder and a writer do together that they couldn't do separately? What can collaboration reveal?

This is a Writer in Residence with more than just writing, but also making. Together we will create books, and what will that teach us about physicality, and words, and form; how will it affect the stories we tell?

The engineer in Manuel seeks perfection. There must be an appropriate way to present each individual thing, someway unique – a book does not always have to be the same as every other. After all, not all words are the same, not all images, not all papers. So the binding should be just as important and unique.

And perhaps this goes deeper. Manuel and myself are attached to books in a way that so many people are, they are physical items you hold in your hands and cherish – Some you read once and shelve for the rest of your life, but God forbid it were thrown away, because it still reminds you of that moment. That one time. That girl. That boy.

So how can that relationship change when we explore the digital world?

And is the book really the greatest form of storytelling?

But in order to understand this we must also try to understand what physicality is and explore this. We will remove the grey space between writer and book and see how a writer may connect with a certain type of binding, a way to present, and how that changes what they write. Simultaneously what we chat about, and what we are interested in, we will delve into online.

We will be publishing everything we are thinking about; stories, research, interviews, everything and anything on our minds with the only goal being to explore.

Knitting and chatting. Making and exploring.

My interest is in what language and words can change to offer something else regardless of form. What opportunities does the internet offer for story telling? How can the written word embrace this? How can we reach more people?

Manuel's is in exploration, both of physical forms but also abstract. Any opportunity for something new and Manuel is there. What if digital didn't need to mean 'without physicality'? What if we had the opportunity to explore everything that was on our minds at any one time in multiple different formats and see if there was something new to be done?

So we got together and decided to collaborate. Together we will investigate ideas - knitting and chatting - I will write it all up, and we will publish it online through newsletters, social media, on websites, in physical form, whatever feels right to us. All the time I will be in the studio with him learning, making and then, at the end, something physical, a book, the printed word, and what will we learn in-between?

What this is really about is finding different ways to say things. Embracing the internet, the digital, and routing it in the physical and learning everything we can on the way about physicality and challenging our held beliefs about the importance of books.

We can’t wait to get started.

- Follow us on Instagram, Twitter and sign up to our newsletter to see everything we publish -

Mycelium Books

What could mycelium materials be used for…?

…the potential applications are countless and here at the studio we’re constantly exploring a wide variety of those…

…as, for instance, utilising pure fungal materials as alternative to animal leather, traditionally implemented in book-making.

The Mycelium Books, part of “The Growing Lab - Mycelia” collection, are an ongoing exploration carried out by Officina Corpuscoli in close collaboration with MAZZOTTI BOOKS/London, an independent bookbinding and letterpress studio.

The Growing Lab: http://www.corpuscoli.com/projects/the-growing-lab/

Mazzotti Books: https://mazzottibooks.co.uk/

#Mycelium #Book #AnimalFree #VeganBook #MaterialCulture #Fungi #Craft #Innovation

Regina Gimenez